As I near the end of my penultimate semester in a nearly 40 years long career teaching and working as a university level faculty member, and after experiencing the toughest semester, in terms of my health, of any I have ever experienced, as either a student or a teacher, currently recovering from a severe case of COVID, requiring me to take paxlovid for five days on account of how challenging COVID has been for my multiple immunosuppressed body, I have been thinking about an important matter that resonates well with the title of this blog, and a key reason why I years ago chose to title this blog as such.

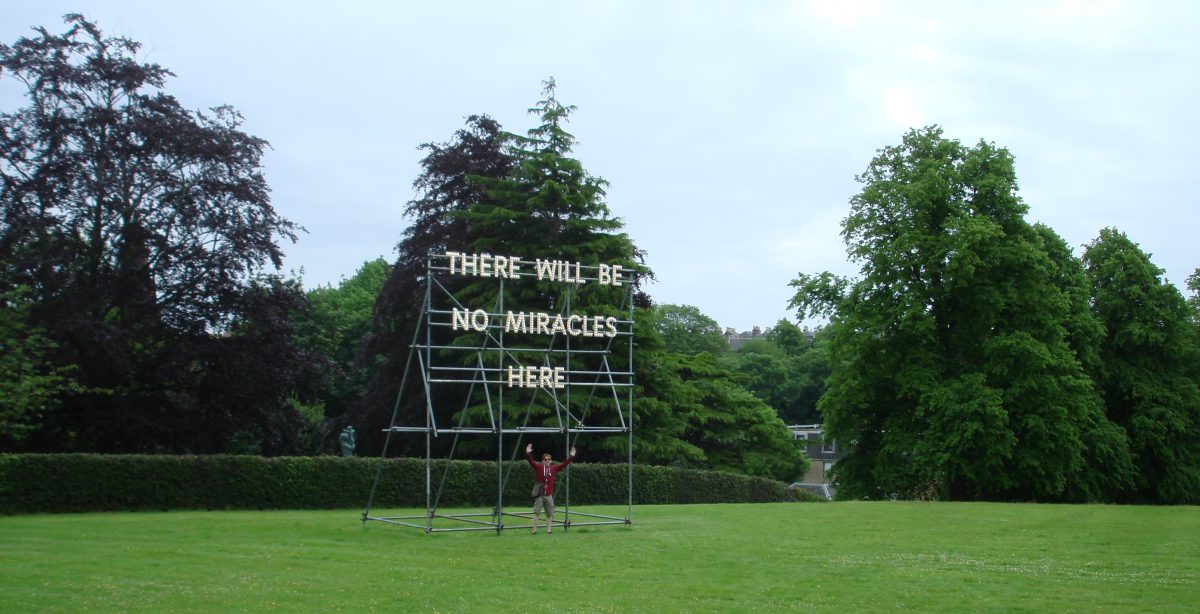

Teachers, at all levels, including at the university, especially at teaching-intensive and teaching-emphasis institutions like UW-Eau Claire, often face the pressure to perform miracles. We are often expected to reach every student in every class we reach, such that we enable every student's experience working directly with us to be transformative and for all of them to leave the class firmly convinced that this has been a great class and we have been great teachers. When students don't so respond, and are not so responding, we have intuited the expectation that this is our responsibility and we must do everything we can to make up for it. No semester, in no class, is ever fully a success until it achieves this miraculous standard of perfection. I know I have internalized this expectation and pushed myself hard, and unreasonably and unjustifiably so, to meet this goal. For instance, whenever I am reviewing students' final work for a class, at the end of a semester, if it does not seem all that impressive, I have learned always to accept this is on me, and to come away convinced I should have done better, while I also need to strive, assiduously, to do better in the next semester.

An unfortunate consequence for me, and undoubtedly many other teachers as well, is we thereby neglect taking adequate care of our health and well-being, along with failing in attending to enough diversity, enough balance, in our full life-praxis so as to leave us adequately intellectually, emotionally, physically, and spiritually fulfilled. And, sad to say, we are all too often praised precisely on account of how much and far we neglect all of that to instead ‘give everything we have' to our students and our teaching–praise, for instance, for all the ‘sacrifices' we routinely make, and for our willingness to be exceptionally devoted to helping our students, in numerous divergent ways, everywhere and all the time.

Yes, I have in part resisted this kind of pressure, as I have often taught by granting students considerable space to take charge of their own learning, and to learn by working extensively and intensively, for protracted periods, with and from each other. And I have often directly acknowledged students do all the time often learn much more from fellow students and much more from the rest of their life-experience than they do directly from me as a teacher in a class they take with me, but I still have all too often acted as if I don't take that acknowledgment seriously.

I do think many of the health problems I have experienced that have cumulatively grown more and more serious and substantial over the past nearly forty years' time result from me pushing myself to strive to achieve the impossible, and so pushing myself yet over and over and over again.

This is all rather strange as when I think back to my own experience as a student I often learned a great deal from fellow students, and from the rest of my life-experience, more than I did from teachers and in classes, while many of the teachers from whom I learned the most, and whose teaching left the strongest and most lasting impact with me, were not teachers who exercised that kind of impact with all of their students. Not at all. Many of these teachers were even unpopular with a significant number of their other students.

Yes, it is worth trying to reach everyone and trying to make a learning experience valuable for everyone, but teachers need to recognize and accept this is not often going to happen, and that does not mean we have ‘failed'. We need to recognize our limits, and recognize students' limits, accepting both for what they truly are.

This past semester, to recount a more specific example, one student early on confided to me that they were highly disappointed in our class as they were not learning anything they found to be valuable, especially anything they found they did not already know. They were looking instead, explicitly, for a ‘revelatory' and indeed ‘miraculous' experience, but not finding it. Initially I felt badly about this, as if I had failed them. But as time proceeded, I determined that the student's expectations of me, and of our class, were unrealistic and unjustified. I did take into account their positions, and their criticisms, by opening up as much space and creating as many opportunities as I could for them to represent their critical positions in class and to otherwise pursue independent areas of strong personal interest and value–as much space as conceivably possible without fundamentally altering the nature and focus of the class for everyone else. Every other student in the class responded positively to what we were doing together while finding the class to be highly enlightening and usefully provocative. But what I too frequently had learned, through my many years as a teacher, is not to focus on the latter but instead to focus on the former–i.e., not to take any satisfaction from the latter but instead concentrate on dissatisfaction associated with the former. Eventually though, and sooner than most semesters, I reflected on what was happening here, for me, and determined I don't need to feel this way. In fact it is harmful.

Institutions need to do a much better job at not encouraging, and not rewarding, this kind of mindset, among teachers working at these institutions.

In a recent article I wrote for the UWEC English Department website and newsletter, announcing my forthcoming retirement, I concluded as follows:

It is up to others to determine what my legacy might be, and what kind of impact I might have left. I will simply add that I have worked extremely hard as a professor, I have given it everything I had and often enough much more than I could afford to give; I have strived continually to do better and to be all the more useful to others with whom I work, especially in teaching; I have never become complacent and taken for granted any level of achievement by instead constantly experimenting and innovating as well as pursuing new passions, interests, concentrations, and emphases in new ways as well as new directions; and I have always strived to do what I do as a matter of principle as opposed to pragmatism. I hope I have contributed in some useful ways, through my own actions, while working here at UW-Eau Claire and for nearly 40 years as a university faculty member, in the long and challenging process of creating a genuinely substantial culture of empathy and solidarity; of embracing active responsibility for collective well-being, of each for all and of all for each; and of drawing upon shared vulnerability as a source of, at least prospectively, the greatest strength.

I think all of that is sufficient, as a useful legacy, but I also believe my legacy includes functioning as ‘a warning'–of the damage that can happen if and when as a teacher one internalizes the expectation that nothing short of perfection is ever good enough, and that you can never do or give enough to the work you do as a teacher.